Keeping Track Through Wing-tagging

Maybe their mothers can tell ‘em apart, but to the human eye, most Turkey Vultures look pretty much the same. We need to be able to identify an individual bird to know just who it is, where it is, and what it’s up to.

With this in mind, in 2012 we began wing-tagging Turkey Vultures as part of a long-term assessment of the health of avian scavengers in the coastal Pacific Northwest. Our red tags with letter-letter codes are quite visible. You can see them from afar with the naked eye. Use your binoculars, spotting scope or camera with telephoto lens to read the fine print!

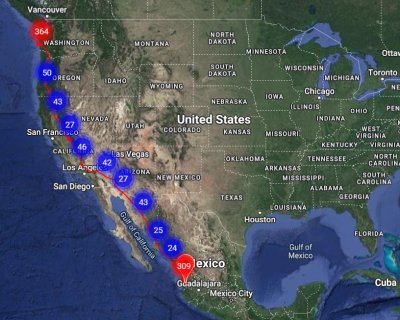

Coastal Raptors and collaborators tagged 54 vultures from 2012 to 2016 on the Washington and Oregon coasts. As of December 1, 2023, 31 of these individuals (57%) had been resighted at least once. Some re-sightings are made by the public who report their re-sightings directly to me. Other reports come to me from people who report their observations online to the USGS Bird Banding Lab (BBL). These observations, 301 in all by December 1, 2023, reveal that many of our tagged vultures are long-lived and site faithful, returning in spring and summer to areas near where they were tagged.

We’ve even received reports on the whereabouts of a few of our tagged birds on their wintering areas. Winning the prize for traveling furthest among our tagged-only birds (no transmitters) is vulture AT, a bird that migrated to a location 80 miles northeast of Guadalajara, Mexico from its tagging site on the southern Oregon coast near north Port Orchard.

Keeping Track Through Telemetry

Transmitters Deployed in 2018

To obtain a more complete picture of Turkey Vulture site fidelity and migratory patterns, we’ve gone high-tech in recent years! Working in close collaboration with the Pennsylvania-based non-profit Hawk Mountain Sanctuary Association, in June of 2018 we tagged four Turkey Vultures with solar-powered, back-pack-mounted GPS satellite transmitters. We gave the vultures names: Airy, Artful Dodger, Grayland and Coy.

Airy flew 30 miles north to Quinault Indian Nation lands after release. Two months later we stopped receiving signals from Airy’s transmitter. Our last transmission came from just outside Tahola, Washington. Coastal Raptors volunteer Glenn Marquardt and I drove to that location, finding elk carcass remains and a dead vulture not far away. A Quinault Natural Resources employee who accompanied us to the site said at the time, “They shoot vultures around here”. The dead bird was not wearing a wing-tag or a transmitter, so we concluded it was not Airy. Nevertheless, we suspect that Airy was shot.

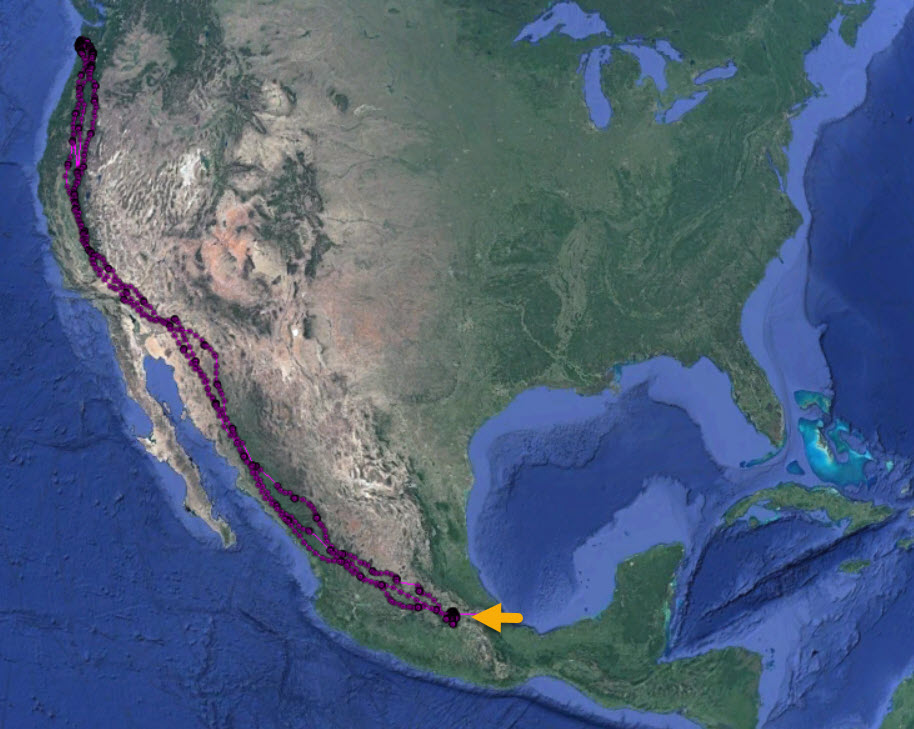

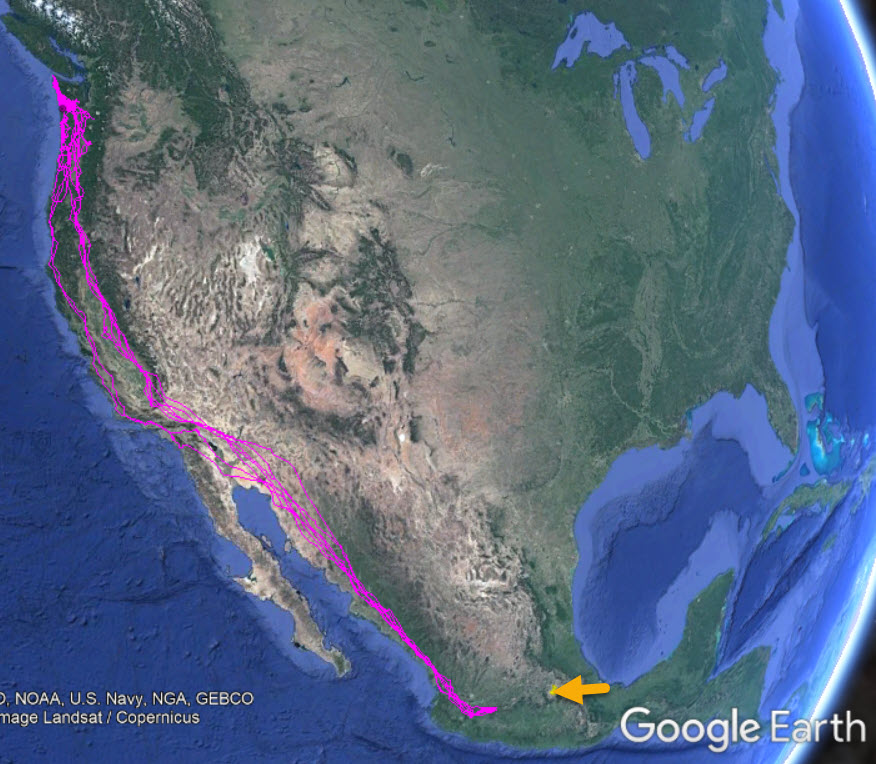

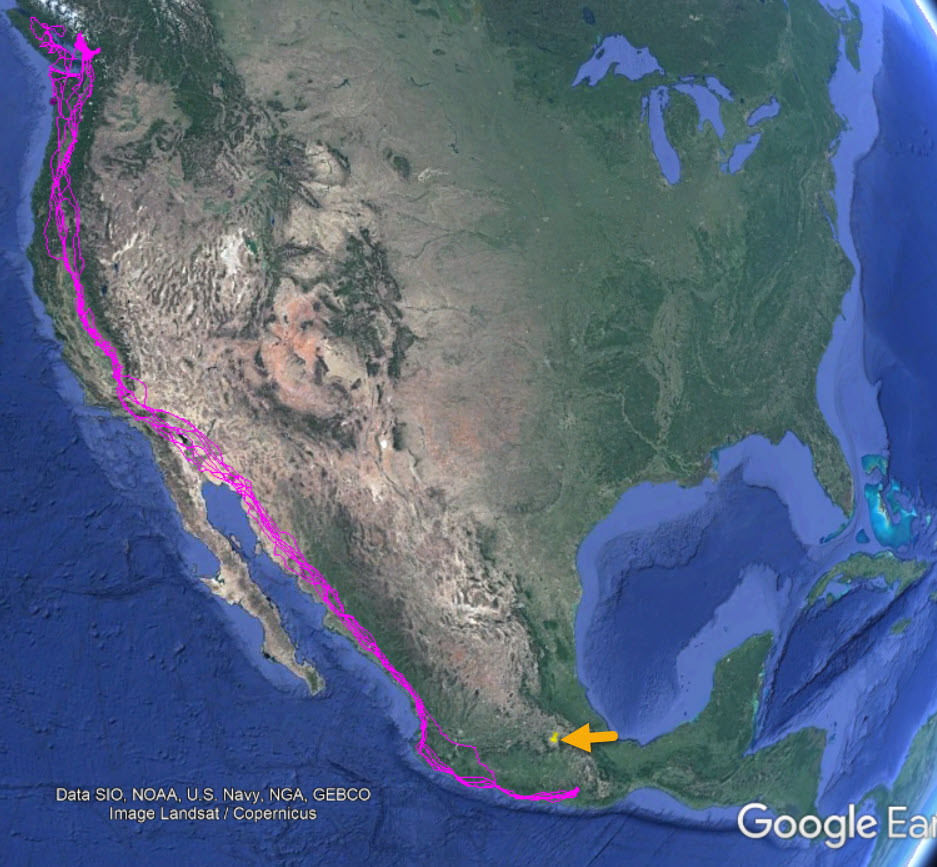

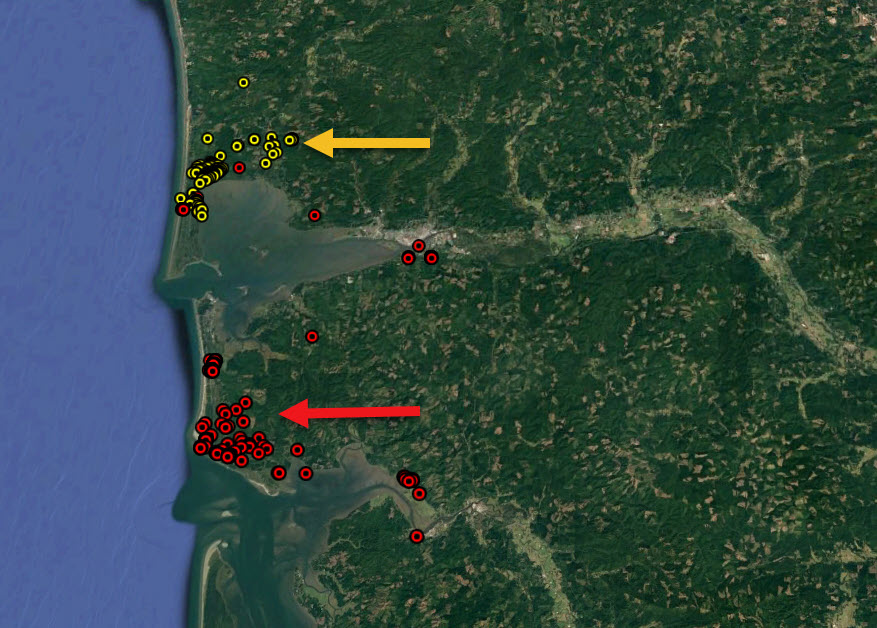

Annual movements of Turkey Vultures Artful Dodger, Grayland and Coy (they do not travel together) are shown below. The yellow arrows on the maps point to Mexico City, Mexico. In the spring of 2024 Coy and Grayland made their sixth migrations north from their wintering grounds in Mexico since fitted with transmitters in 2018. Grayland spends spring, summer and early fall in southern British Columbia while Coy shows the same seasonal pattern in western Washington.

Artful Dodger made two migrations to Mexico for the winter. In March of 2020, 643 days after the first transmission, Artful Dodger’s story ended when his remains were found on a cactus farm 30 miles northeast of Mexico City. Traveling for hours from their home in Xalapa, Mexico to the last known location was Kashmir Wolf and his wife Diana Balbuena. Kashmir, Veracruz River of Raptors Monitoring Coordinator, was asked to search for Artful Dodger by Hawk Mountain Sanctuary’s Director of Conservation Science Laurie Goodrich. Kashmir and Diana found several bones, feather remains, plus the wing-tag and transmitter; they did not find clues to the cause of death.

Transmitters deployed in 2022

In 2022 Coastal Raptors fitted transmitters to three more Turkey Vultures and named them Walter, Don and Amelia. These transmitters, purchased by Cellular Tracking Technologies, send location information to cell phone networks rather than to satellites as did the transmitters we deployed in 2018.

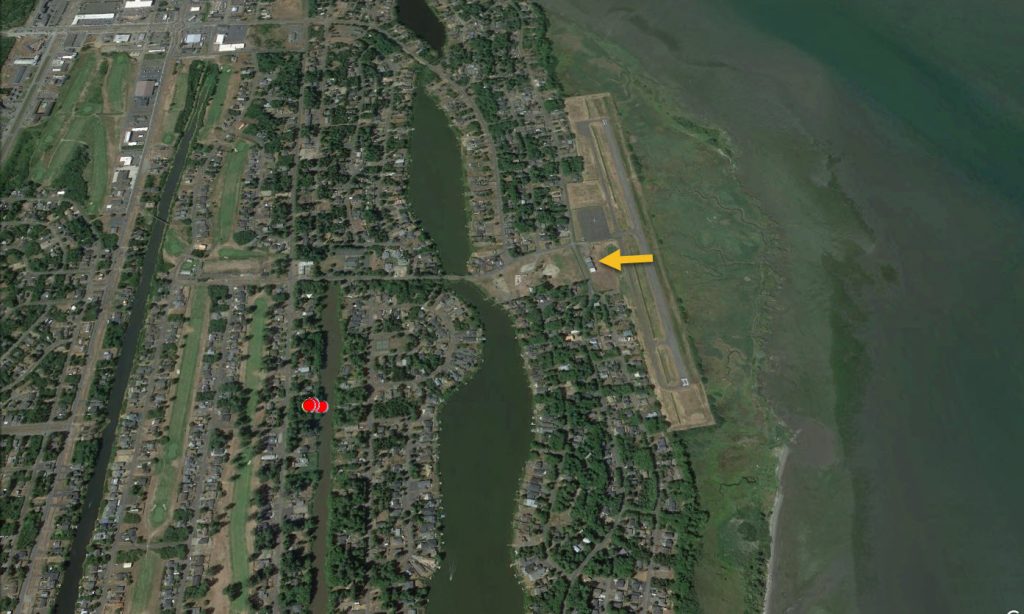

We trapped them in July and August at the airport in Ocean Shores, Washington. Within days of release, we were concerned about the status of Walter and Amelia since the tracking data we were receiving indicated that they were not moving. Sadly, we found Walter dead two miles from his release location on the north side of Grays Harbor. We were unable to determine the cause.

We followed Amelia’s last known location to a vacant lot a half-mile from where she was released. The lot is highly vegetated and includes many tall conifer trees. We searched the property thoroughly in summer and fall and were unable to locate the transmitter/Amelia.

In January of 2023 we got a break. For more detail see my blog post Turkey Vulture Amelia Soars Free.

Don was a bright spot in our 2022 Turkey Vulture tracking initiative. Don made his way to Mexico in fall and was wintering near Nayarit, Mexico when his transmitter stopped working.

Transmitters deployed in 2023

Coastal Raptors fitted ransmitters purchased from Cellular Tracking Technologies to two Turkey Vultures in April. One we named Caeden, after the youngest of our field team, the other Glenn, after the oldest. We also fit both vultues with wing-tags (Caeden with CM and Genn HJ).

We trapped them at the Ocean Shores airport, Caeden on April 29 and Glenn on April 30.

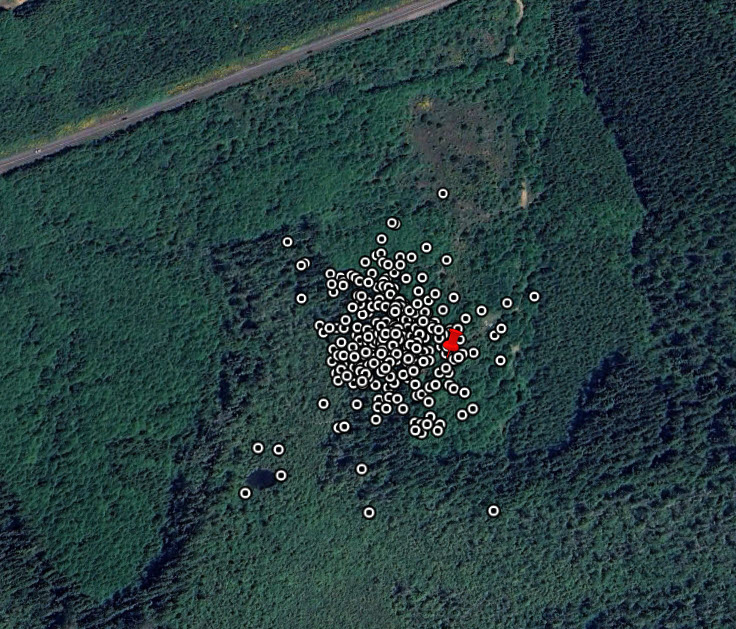

Caeden’s transmitter continued to transmit GPS fixes from May 12 to 20. On May 20 GPS fixes stopped because the voltage on the solar-powered transmitter dropped below the threshold for sending location points (threshold is 3.850 Volts).

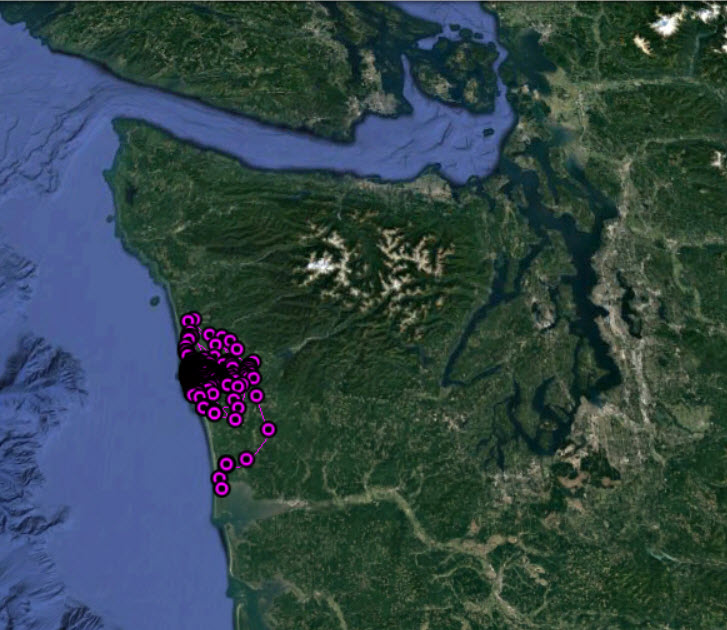

The location where the signal was lost is dense forest (map to the right). I searched the transmitter location points several times in June and early July, focusing on the area shown by the red pin. I wasn’t successful in my search.

My hope at the time was that Caeden was flying free, having removed his transmitter. It turns out Caeden was observed alive and well, sans transmitter!

On July 14, Caeden was sighted feeding on a deer carcass on the Ocean Shores peninsula. For that story, go to Third Turkey Vulture Sheds a Transmitter.

On June 26, Glenn’s transmitter was found on a stump in a clearcut about 18 miles southeast of the deployment site at the Ocean Shores airport. For the full story, go to Shoalwater Tribe DNR Locates Vulture-Shed Transmitter.

In hindsight, it appears that we had secured the transmitters too low on the back, which allowed these vultures to reach behind and bite through the Teflon harness (see Misfits – Incorrectly Fit Harnesses Led to Turkey Vultures Shedding Their Transmitters!).