Scavengers

We begin this page by defining just what a scavenger is. Dictionary.com offers these alternatives. You find the best fit.

- An animal or other organism that feeds on dead organic matter

- A person who searches through and collects items from discarded material

- A street cleaner

You are correct!

Of course most of us know what scavengers are and what they do. Best known among the scavengers are the vultures. Vultures are dependent on finding and securing carrion, dead organic matter, to survive. As such, they are known as “obligate scavengers.”

You might be surprised to learn that many other bird and mammal species rely on carrion as a component of their overall diet. These opportunists are known as “facultative” scavengers.

Scavenger Monitoring

In 2011,Coastal Raptors and collaborators began work on a multi-year study to examine contaminant and disease exposure in three species of avian scavenger in coastal Washington and Oregon: the Bald Eagle, Turkey Vulture and Common Raven. These birds occupy important positions at the apex of the coastal food web. Accordingly, their health reflects the health of the larger avian communities in which they live.

An important goal of our research was to evaluate the risk of exposure to contaminated food sources in the critically endangered California Condor, a species targeted for reintroduction in the PNW as our project was getting underway. California Condors once occurred along the Pacific Coast from Mexico to southern British Columbia.

Years in the planning, the Yurok Tribe now leads an effort to restore California Condors to their former range in the Pacific Northwest. You can read about their efforts here.

Captures

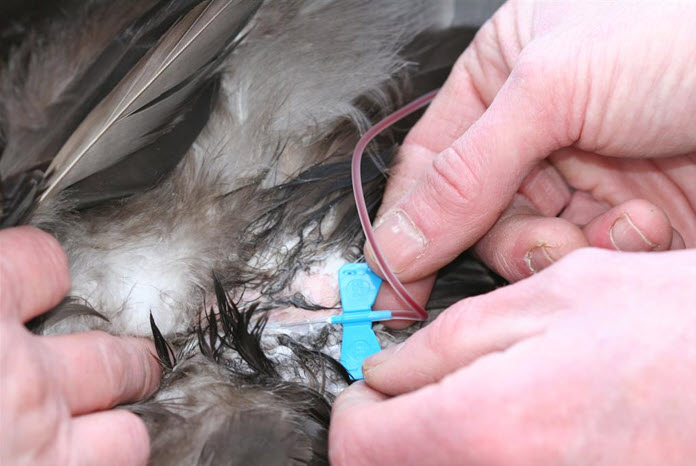

We use a bow net (left two photos) or a net launcher to capture Bald Eagles, Common Ravens and Turkey Vultures for sampling.

Color Marking

We identify individuals captured for the research by fitting them with colored leg bands or wing tags.

Sampling for Contaminants and Disease Pathogens

While our trapping and sampling effort began with a few captures on the Washington coast in 2011, most of the field work for this project took place from 2012 to 2015. We continue trapping and sampling a few avian scavengers for avian influenza and hemoparasite screening each year.

Contaminants. We’ve sent samples from 32 Turkey Vultures, 28 Bald Eagles, and eight Common Ravens to labs to test for one or more organochlorine compounds (DDT, aldrin, dieldrin, and PCBs), lead and mercury).

Disease Pathogens. We’ve sent samples from 27 Turkey Vultures, 23 Bald Eagles and eight Common Ravens to labs to test for one or more of the disease pathogens identified below.

- Coxiella burnetti

- Avian influenza

- Paramyxovirus-1

- Sarcocystis

- Mycobacterium

- Chlamydophila psittaci

- Salmonella

- Brachyspira

- Mycoplasma

- Adenovirus

- Hemoparasites

The bacterium C. burnetti causes Q fever, a worldwide zoonotic disease. The bacterium has been detected in Pacific Northwest marine mammals. Coastal avian scavengers are at risk of exposure to the C. burnetti when they feed on marine mammal carcasses. We sampled 15 Bald Eagles, 25 Turkey Vultures and 6 Common Ravens for C. burnetti, 2012-2014. The veterinary lab at Colorado State University ran PCR tests on our samples. All tests results for C. burnetti were negative.

Test Results

Results on lead and mercury exposure in Turkey Vultures and Common Ravens in the study are published in the journal Environmental Pollution. This research paper is available here and on the website Publication page.