I’m pleased to share that co-authors and I published a scientific paper on Peregrine Falcon abundance in the September 2025 issue of The Journal of Raptor Research. For a copy, click here. Below I provide an overview of the study, drawing from text and graphs in the published report.

Title: Estimated Annual Abundance of Migratory Peale’s Peregrine Falcons in Coastal Washington, USA

Authors: Dan Varland, Joe Buchanan, Guthrie Zimmerman, Javan Bauder, Tracy Fleming, and Brian Millsap

Introduction

The Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) has a nearly global distribution consisting of 18 – 20 subspecies, most of which were substantially impacted by the effects of environmental contaminants in the twentieth century. Widespread conservation actions led to species recovery and delisting of two North American subspecies – F. p. tundrius and F. p. anatum – identified and protected under the Endangered Species Act. The Peale’s Peregrine Falcon (F. p. pealei), with a distribution limited to the Pacific Coast of North America, was not ESA-listed but was protected under a similarity of appearances clause in the Act.

Peale’s peregrines are larger and more heavily pigmented than other peregrine subspecies. For more on Peale’s peregrines, see The Peale’s Peregrine—A Quintessential Coastal Raptor at Bird Man Dan’s Blog.

Following Peregrine Falcon delisting in 1999, the US Fish and Wildlife Service began a process to allow “take” (capture) of wild peregrines for falconry in the United States. Recently, that effort involved generating updated estimates of the collective abundance of the three North American peregrine subspecies. Because of the more limited distribution of F. p. pealei, we conducted an analysis specific to its geographic range.

Study Area and Methods

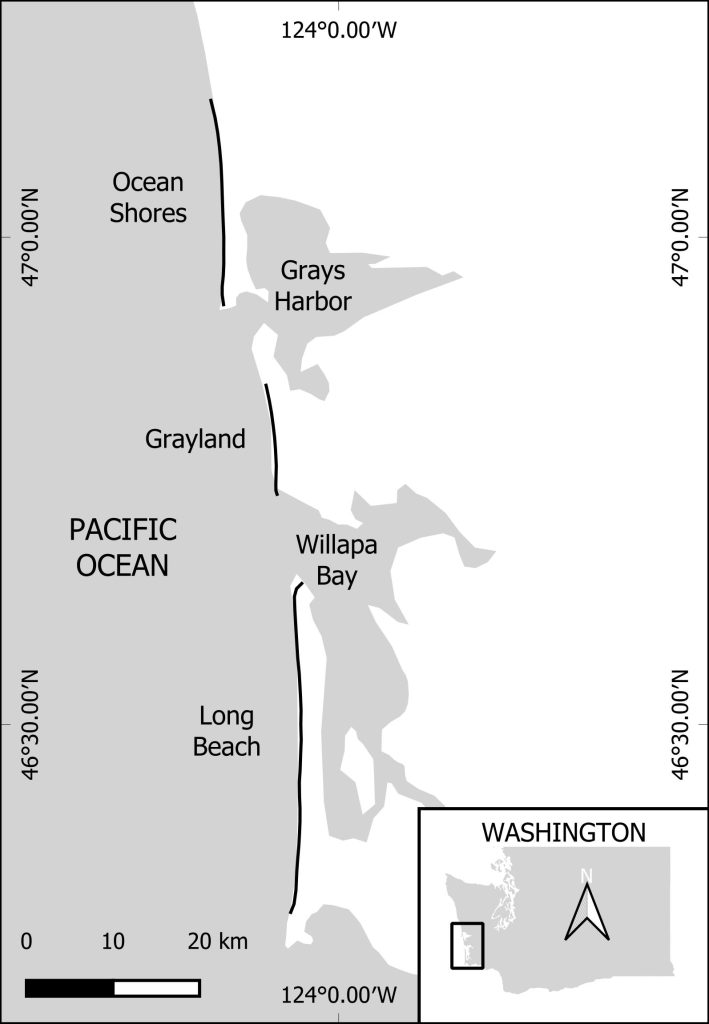

To this end, we analyzed data from a long-term banding and resighting program on three beaches on the southern coast of Washington to estimate the annual abundance of migrating and overwintering F. p. pealei using the capture histories of 250 Peregrine Falcons, nearly all of which were captured during more than 1,000 vehicle surveys between 1995 and 2024. Because we studied an open population of migratory individuals to estimate annual abundance we employed a novel approach to population modeling.

Results

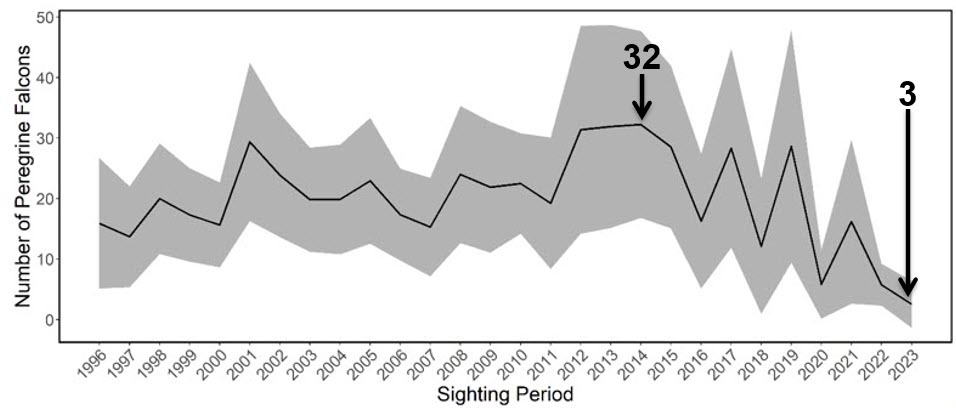

The vast majority of the Peregrine Falcons that we captured and banded on study area beaches over the years were the Peale’s subspecies (79% of 241 identified to subspecies). Annual abundance of Peregrines increased from the 1996-1997 sighting period to 2012-2014, and then began to decline.

The graph below shows model-estimated Peregrine Falcon annual abundance. The highest abundance estimate for Peale’s peregrines was 32 falcons during the 2014-2015 study period and the lowest was three falcons in 2023-2024.

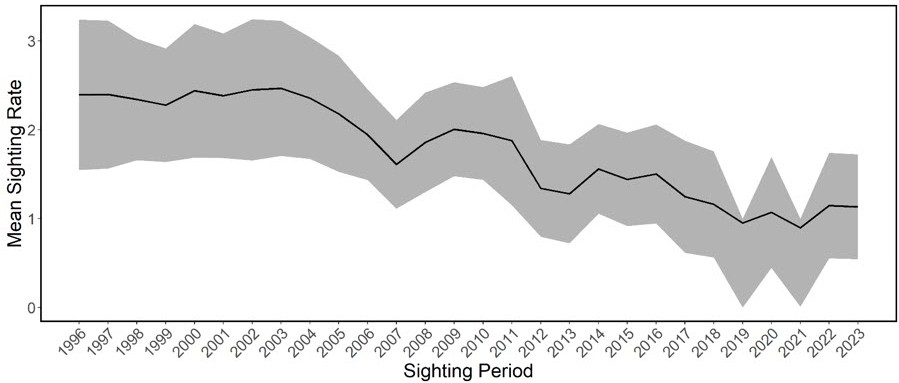

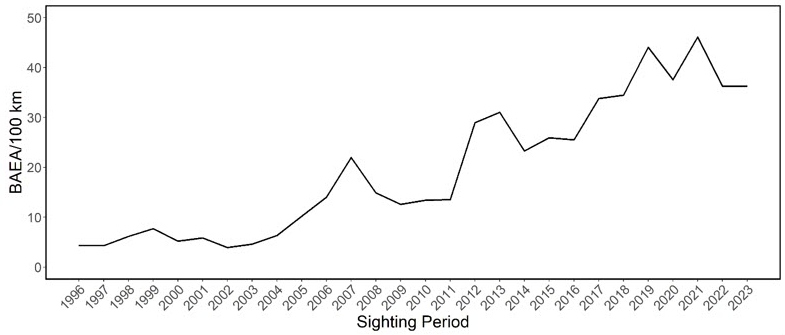

As Peregrine Falcon sighting rates decreased, Bald Eagle encounter rates increased. The graphs below show the model-averaged sighting rates for Peregrine Falcons and the number of Bald Eagles observed per 100 kilometers driven over the 29 year study.

Peregrine Falcon sighting trend.

Bald Eagle sighting trend.

Discussion

We suspect the change in sighting rate was a behavioral response by Peregrine Falcons to the threat of kleptoparasitism (food stealing) by Bald Eagles. The photos below show a Peregrine Falcon feeding at the Ocean Shores study area beach when its prey is spirited away by a Bald Eagle.

Although identifying other causal factors for the downward trend in Peregrine Falcon abundance at the end of the study period was beyond the scope of the project, among the potentially relevant factors was exposure to highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). HPAI exposure occurs when peregrines feed on wild birds contaminated with the virus, including coastal gulls, terns, geese, ducks and shorebirds.

In 2014, HPAI H5N8 was the cause of death of one of our banded falcons, the timing of which coincided with the highest abundance of Peregrine Falcons during our study (2014-2015). In 2021, a strain of the virus far more virulent to wild birds, HPAI H5N1, was detected in eastern North America, and subsequently spread continent-wide to the Pacific coast. While we have no data to suggest that the presence of H5N1 affected falcon abundance on our study area, annual abundance of peregrines was lowest during the 2022–2023 and 2023–2024 sighting periods when wildlife mortality from HPAI was increasing significantly across North America.

Conclusion

Our findings add clarity to the migration and overwinter abundance of F. p. pealei on the Washington coast and may inform decisions about the take of this subspecies for falconry.

Note: If you would like to see more of my Blog posts on Peregrine Falcons, click on Pacific Coast Peregrines below.