Since 1995, I’ve been conducting raptor surveys by vehicle along Washington’s coastal beaches. Completed with a host of volunteers, the surveys take place every month from September to May. It’s not unusual for us to come across sea lion, seal and the occasional whale carcass that washed ashore. We record these observations along with data on the raptors that we see with the understanding that marine mammal carcasses are important food resources for scavenging raptors.

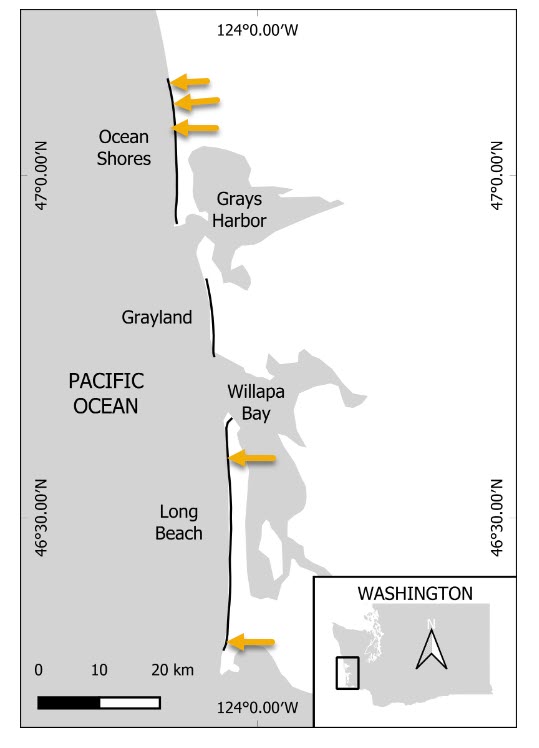

During a survey on May 30 at Ocean Shores we encountered three dead Gray Whales at the north end of our survey route. I show their locations on the map below as well as the locations of two dead Gray Whales that we observed during raptor surveys at Long Beach, one on April 6 and another on May 18.

Given their size, whale carcasses take a long time to decompose. We usually see them for months following our first encounter. We’d detected two of the three whales that we saw on May 30 during surveys earlier in the spring.

Jessie Huggins

I had become aware of the unfortunate situation with Gray Whales through an article in The Daily World, my local newspaper. Then after finding three dead whales on the same day, I decided to give Jessie Huggins a call to find out more; Jessie’s the marine mammal stranding coordinator for the non-profit Cascadia Research Collective based in Olympia, Washington.

“Right now in Washington,” said Jessie, “we’ve had 13 dead Gray Whales that we know about. Our average is between six and ten, so we are above average.” The total included twelve individuals found on the outer coast and one from inland, Puget Sound.

Jesse had necropsied the three whale carcasses that we saw at Ocean Shores. One was yearling-sized and appeared to have died from a Killer Whale attack. The other two, both adults, were extremely emaciated and showed no signs of illness or trauma. Their deaths were attributed to starvation.

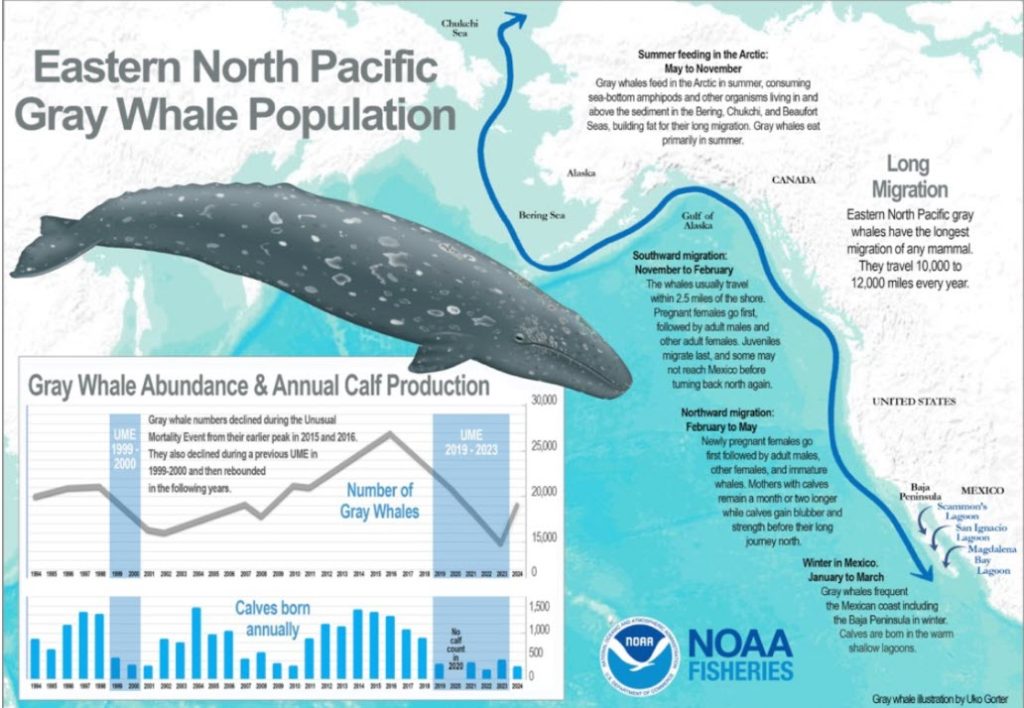

Gray Whales migrate 10,000-12,000 miles annually, swimming between breeding and feeding grounds. Their migration is the longest of any mammal. In the spring the whales migrate north to Alaska after wintering in the warm lagoons of Baja, Mexico. The females give birth there. For summer they migrate north to coastal northern Alaska. Here they feed heavily on invertebrates to re-build their fat reserves after the long journey (see Gray Whale, Wikipedia.)

Unusual Mortality Event

The population of Gray Whales of the Eastern North Pacific has dropped dramatically in recent years. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) described the die-off as an Unusual Mortality Event (UME); it extended from 2019 to 2023. During this time NOAA estimated that the Gray Whale population declined from 20,500 to 14,500 individuals. Furthermore, NOAA estimated that breeding ground calf production dropped from 950 to 400 individuals during the UME. The graphic below shares the story of Gray Whale migration and the drop in numbers (for more from NOAA on this, click here.)

According to NOAA, the common cause of the die-off was a significant reduction in the quantity of food available for the whales. Warming of arctic and subarctic waters due to climate change resulted in a reduction in sea ice which, in turn, meant decreases in marine algae inhabiting the ice. As the algae dies, it falls to the sea floor and becomes food at the bottom of the food chain. Further up the food chain, invertebrates feed and then become food for Gray Whales.

I asked Jessica whether the elevated Gray Whale mortality rate in 2025 was a consequence of poor forage conditions on the arctic summer grounds. “Yes,” she said, “it appears to be a continuation of the problems that we saw during the mortality event: really skinny whales and food web issues in the arctic.“

The spring whale die-off in 2025 took place all along their migration route. In San Francisco Bay, for example, six Gray Whales were found dead during one week in May.

“We’re just not seeing them being very successful right now,” said Jessie. “And there may even be a reopening of the mortality event.”

After reading my post, Don Schreiner of Rockford, Illinois wrote, “So sad to see the current trend with the Gray Whales. Hopefully this is temporary and their food supply bounces back to its normal cycle and a future blog will speak to the reduction of deaths.” How true.

Raptor Count, May 30 Survey

We counted four Turkey Vultures, all feeding on a sea lion carcass. Three stopped to give us a look as we approached in the vehicle to get a photo (all photos below by Tom Rowley.)

We counted nine Bald Eagles, eight adults and one juvenile.

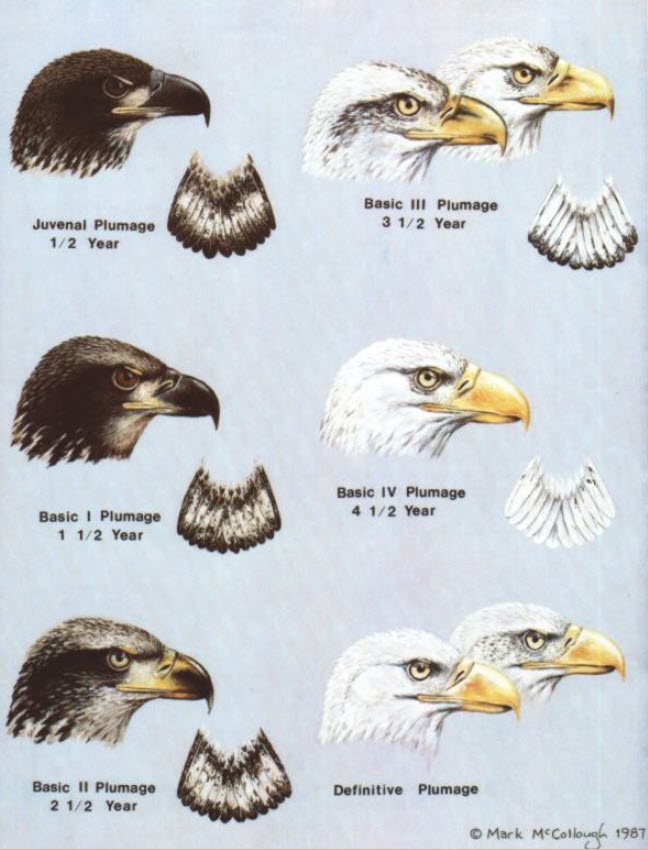

The juvenile we saw is shown below. It usually takes five years for Bald Eagles to reach adult plumage. Backlighting by the sun made eye, beak and plumage coloration hard to discern (characteristics we use for aging).

Later in the survey we saw this eagle under better light conditions. Given the yellow eyes, the beak color in transition to yellow, and the mix of white in the plumage, we thought this one was two years old.

4 responses to “May 30 Raptor Survey Reveals High Mortality of Gray Whales on the Washington Coast”

Thanks for the good read, and the Cameo. We sure did have a good time! Ryder’s last day of school was Tuesday. We were recapping his favorite parts of the school year while en route to his final day. Wouldn’t you know it, the Raptor Survey made the top five. Thanks again Dan.

Well written and very depressing as I don’t think we can reverse warming. I have always believed whales are as intelligent as humans…if not MORE so. Imagine knowing what is going on and not being able to save yourself.

I also noticed the article on the grey whales in the Daily World. Thanks for taking it the extra step. Nice picture of the crew.

Very interesting Dan, thank U for yr work