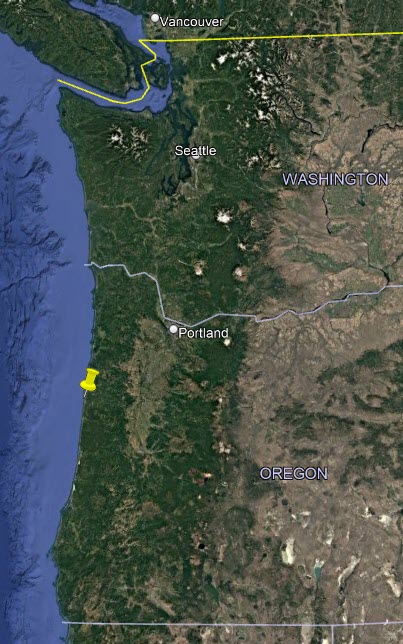

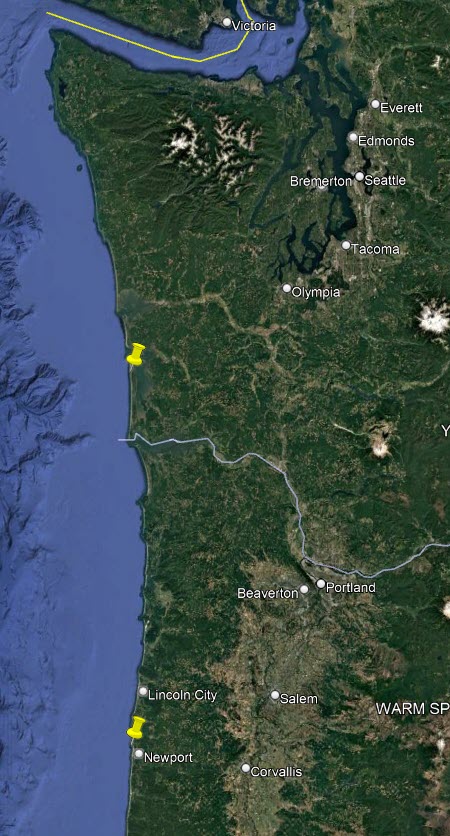

I first got to know Roy in 2010 when he contacted me about a banded Peregrine Falcon that he’d photographed circling the lighthouse at Oregon’s Yaquina Head Outstanding Natural Area. Through Roy’s photos, we were able to determine that this peregrine was one of ours, wearing visual ID band C/5.

In September 2024, I received an email and photo from Roy regarding a banded Peregrine Falcon that his friend Chuck Philo had photographed. “We’d appreciate knowing if this is one of ‘your’ birds,” wrote Roy.

I was particularly eager to find out if this peregrine was indeed one of ours. Peregrine counts and bandings during our surveys have dropped dramatically in the past few years. We hadn’t had a resighting, away from the study area beaches, of one of our banded peregrines since 2022. What’s more, during surveys on the beaches in 2023 and 2024, we’d banded only two peregrines and resighted just one.

Chuck had photographed the bird lifting off from a tree at Yaquina Head, a location very near where Roy had photographed peregrine C/5 in 2010. Unfortunately, Chuck’s photo was not clear enough to read the code on the visual identification band.

On October 7, Roy contacted me again. “Chuck Philo and my photographer friend Tim Kuhn were at Yaquina Head yesterday, and the banded falcon was back,” wrote Roy. “Tim has great camera gear and got some photos of the bands.”

Positive ID!

The falcon wore visual identification band E/7. This was one of our birds! (For more on the banding protocol we use, see Marking Techniques).

We had banded E/7 on the Long Beach Peninsula on October 29, 2017. At the time we determined that she was age one, based on several juvenal feathers that we saw in the plumage on her back. It was our first resighting of this peregrine, now eight years old.

“We’re out at the lighthouse almost every day” said Tim Kuhn in a phone coversation with me. “We’re always looking for something out of the ordinary. We see many difference species, and occasionally find one with bands on it. It’s always fun to report and find out about them, especially falcons.”

Altogether Tim, Roy and Chuck photographed E/7 on nine occasions from October 6 to November 7, 2024.

October 12. “The flock in these two shots had two green-winged teals leading,” wrote Tim in an October email. “As you can see, E7 flies past the scoters and attempts to take a teal. She missed in this case. This is a pattern we have seen her do time and time again, attack a mixed flock and try for the teals.”

The last reported re-sighting of peregrine E/7 was November 7, 2024. In response to an email I sent to Roy asking whether his group had continued to see E/7, he wrote, “We’ve had some stormy weather over the past week which is not conducive to hanging out at the headland. FYI, about two weeks ago an adult peregrine was picked up on the beach in Newport and died in route to a rehab center. It was confirmed avian flu!”

It’s entirely possible that E/7’s disappearance is the result of death due to the deadly, highly pathogenic form of avian influenza (HPAI). HPAI is prevalent among wild aquatic birds, including gulls, terns, geese, ducks and shorebirds, peregrine food sources.

An outbreak of HPAI was confirmed in wild birds in Washington 2022. The pathogen continues to spread through wild birds, mammals, poultry, livestock and more throughout North America.

The 47-second video shows a Western Snowy Plover in distress. He/she is unable to stand and can only fly short distances. In all likelihood, this plover was suffering from exposure to HPAI. The video was taken during a Coastal Raptors-led raptor survey of the Long Beach Peninsula on November 4, 2024. In the last part of the video, Caeden Gaffney, Scott Horton and I try to capture the plover for avian influenza testing. Unfortunately, the plover flew west, landed in the ocean and was pulled away from shore by receding waves.

In this blog I wrote about the dramatic drop in counts, bandings and resightings of peregrines that we saw during our raptor surveys on the Washington coast in 2023 and 2024. In 2025 co-authors and I plan to publish a science-based research paper documenting a decrease in the abundace of Peregrine Falcons on our study area beaches. Our analysis points to a long term increase in Bald Eagle numbers as the cause. That said, it’s likely that some of the recent decline in peregrine numbers is in part due to peregrine exposure to HPAI through feeding on virus-infected prey.

I’m grateful to Roy Lowe, Tim Kuhn and Chuck Philo for informing me of the presence of Peregrine Falcon E/7 on the Oregon coast in 2024.

Note: If you would like to see more of my Blog posts on Peregrine Falcons, click on “Pacific Coast Peregrines” below.

2 responses to “Long-lost Banded Peregrine Sighted on the Oregon Coast”

Hi Dan, wanted to add my experiences over the past few years on Brady loop rd on the lower Chehalis river tidal plain pertaining to Peregrine falcon sightings.. A fellow birder (Grace Thornton) and I have been discussing our lack of Peregrine sightings as well recently. Grace birds the coast more often than I do (Baycenter, Tokeland, Grayland, Bottle Beach) and has gone without a Peregrine in about a year.. I am on Brady Loop most of the time and I have seen only one early Peregrine (in September 2024) through all of the migration season of shorebirds and waterfowl until now, early April 2025.

Generally, until a few years ago, I would have one and often two Peregrines locally all Winter. The last couple of years things have slowed. Maybe a bit less shorebirds in the mix as well, but noticeable absence. Also, seems to be less juvenile/immature birds in my sightings past 4-5 years.

Merlins are never common but they also appear to be less seen locally in my experiences.. A. Kestrels are doing very well. First Winter without a wintering shrike in many years to add as well.

Ebird reports does have one Peregrine and one Merlin on Brady loop over the psst two months. Pretty quiet stuff.

Sure hope the news gets better on these great birds !

John Raymond

Thanks, John for sharing this information.