The Raptors

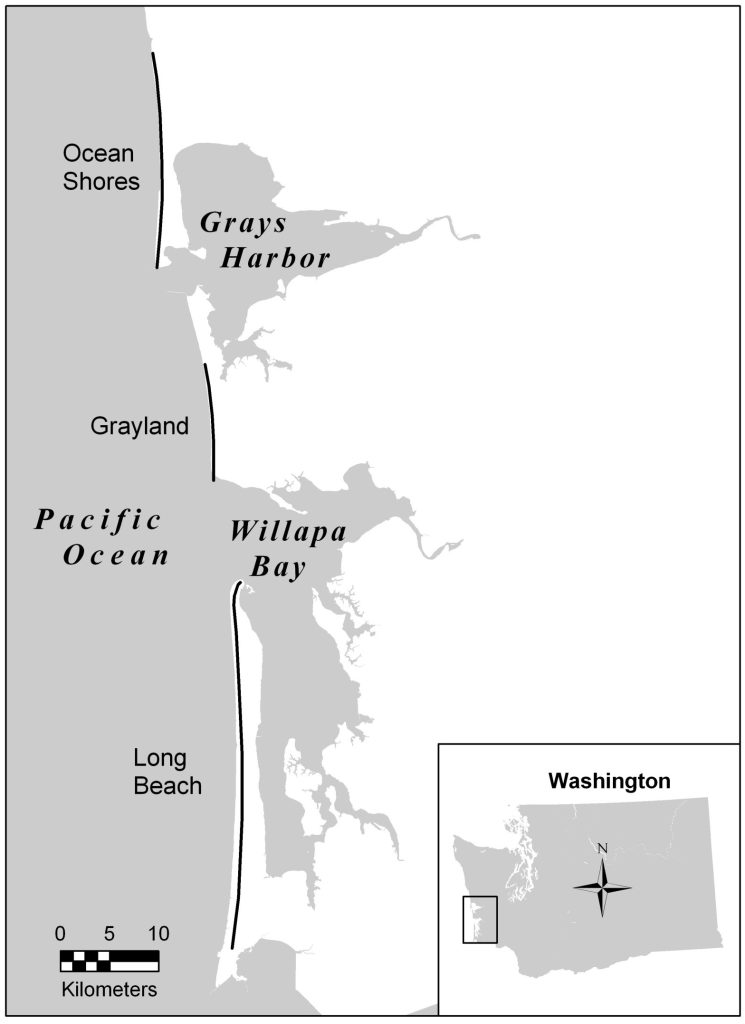

Our beaches near Grays Harbor and Willapa Bay front two of the largest, richest estuaries on the Pacific Coast of North America. Where freshwater and salt water meet, estuaries characteristically support large bird populations. Nick Dunlop’s photo above suggests as much. Grays Harbor and Willapa Bay are ideal locations for shorebirds migrating, in spring and fall, along the Pacific Flyway – and for the falcons eyeing them en route. Our page aims to help you identify the specific groups of birds making up both predators and prey. We sort them by reporting the relative frequencies of raptors we have encountered in nearly 30 years of experience in research.

Bald Eagles, Peregrine Falcons, Northern Harriers and Merlins total 97% of the raptors we see during our protocol-based Complete Raptor Surveys.

The Bald Eagle is the top avian predator on our beaches, making up 59% of all raptors counted during these surveys. They are exceptional predators but we rarely see them in the hunt. They get most of their food through scavenging, an approach that takes much less effort and is less risky than chasing down prey. We regularly see carrion in the form of dead birds, fish and mammals on our outer coastal beaches.

Peregrine Falcons comprised 21% of the raptors encountered during protocol surveys. Shorebirds are a primary source of food for peregrines on the coastal beaches; also important in their diet are seabirds and other types of water birds including ducks, grebes, gulls.

Contrary to popular belief, we’ve also documented that Peregrine Falcons scavenge regularly on our study area beaches. Known to dive at “stooping” speeds in excess of 200 mph, who would have thought that the world’s fastest animal would stoop to scavenging! We’ve seen fewer peregrines in recent years owing, we think, to an increase in Bald Eagles.

Northern Harriers hunt for birds and small mammals above the tall grass covering the sand dunes adjacent to our study beaches. Harriers makes up 10% of all raptors we encountered during protocol surveys. Merlins comprise 7% of the raptors that we encounter. These jay-sized falcons primarily hunt shorebirds on our beaches.

Ten species, featured in the photos below, make up the remaining 3% of raptors that we see during surveys. All are featured in the photos below.

Shorebirds

Shorebirds are by far the most abundant and diverse avian group on our coastal beaches. Each year tens of thousands of shorebirds spend time feeding and resting on the beaches and adjacent coastal estuaries of Grays Harbor and Willapa Bay.

Tom Rowley photo.

Tom Rowley photo.

Tom Rowley photo.

Soo Baus photo.

Soo Baus photo.

Soo Baus photo.

Would you like to learn more about birds? We recommend Cornell University’s Lab of Ornithology.